Copenhagen, 2021

Just three months after I return to Denmark, I receive an email from the leader of a school. It was at the height of the lockdown, and she wanted to know if I could take over a class? The thought of the students without a teacher was enough to make me acquiesce despite the fact that I was really enjoying country living and had sworn, that I would never return to teaching.

After being stranded in New York at the height of the pandemic, I had finally been able to catch a flight back to Denmark. I had three flights cancel and had to wait months before this could happen.

It had now settled into the rhythm of country living. I discovered my natural flows – that I usually awaken at 4:30 am. That I could see the sun rise from my window, as it climbed a sky right above a field. Since I was landless, I figured I could tend to each of my houseplants as if they were caretaking a piece of land for me. In this way, my land was divided amongst them. My house was on a little island and I could see the water from my desk. I enjoyed being surrounded by trees, sky and the great expanse of uninterrupted land as my view. I found myself falling into a rhythm that had little to do with clocks but more to do with the beating of my heart, the pace of my breath and my cat, Popcorn. I now took the time to smell my food before I ate. I learned to savor. The quiet. Each breath. Each stretch. And it was wonderful.

But, despite all of this, I felt compelled to take this job. And besides, it was a temporary contract; I didn’t have to commit to anything long term. And to be honest, I love teaching. I always found my students to be among some of the coolest people I have ever met in my life. I have taken the spiritual path of the wayward, and I pay attention to those who witness and still love.

Getting my students to write about themselves wasn’t about the western trope of “discovering” a literary star –to me, all my students’ writings are interesting and fascinating to read. It was about the students realizing that they could access the tool that writing could be, in processing their own lives and events, finding their own voice, that perhaps they had never had the time or opportunity to reflect on before, and even learn to tell and retell in more powerful and affirming ways. I also want to actively shift away from this individualistic tendency that capitalism seems to breed.

I entered teaching with the idea that the classroom could be a place of vision, solutions and self-actualization. What I found mostly were students struggling in various degrees with sometimes extreme conditions of distress. In an industry that reflected the hierarchical structure of our culture, perhaps I was naïve in thinking that schools could be an instrument of change– but I had always held the idea that education was perhaps, one of the greatest powers there are. But the question is, what kind of education? Is it an education that affirms and even celebrates its student body, acknowledging its diversity in experiences? Or punishes them, for being different?

I’m not only speaking along ethnic lines either. A few years ago, I learned from a Danish radio programme that many Danish students, in Danish classrooms did not participate in class discussions themselves. Apparently, the fear of saying something wrong was an even more efficient muzzle than any.

So, with all of this in mind, I packed up my suitcase and took the over two hour train ride into Copenhagen. I was going to stay with my friend Ida, with her and her family in their Copenhagen home. As my oldest friend here, it was like staying at a favorite relative’s home. From her home, I would walk the twenty minutes along the lake to work every morning, the streets emptied of people by the pandemic.

The first few months I had to conduct my classes over Zoom. I didn’t think I would have ever been in this position. To be honest, my modus operando for the pandemic was ‘lay low’. I had absolutely no reason to be out there in the real world – I wasn’t an essential worker and besides, withdrawing from the world is a social tic of mine.

At first, it was difficult – but most of the students attended the Zoom classes. Gradually, the school started to open back up, with half of the class attending on alternate days.

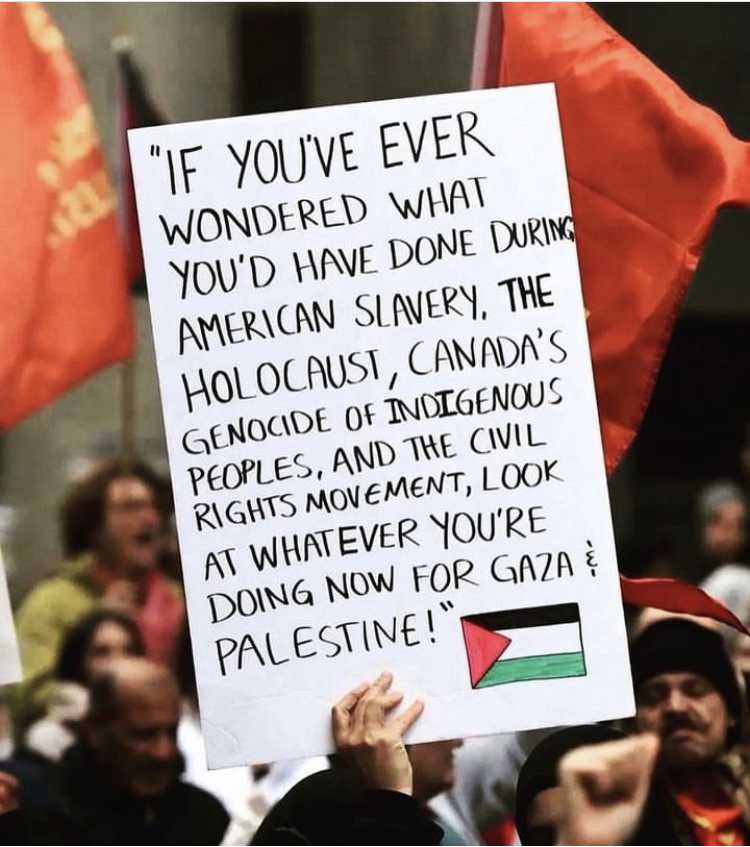

Noerbro is the most colorful neighborhood in Copenhagen – the streets a perfect reflection of the many worlds thrust together by displacement, war and its indigenous population of young professionals, students and families. Historically a poor Danish working-class neighborhood, its residents of yore would be hard-pressed to recognize it today. On Blaagaardsgade, flying above this busy pedestrian street, is a banner colored red, black and white as in “Free Palestine!” Arabic greengrocers sell vegetable samosas along with plantains, okra, and cassava while cafes shelter the city’s superfluous student demographic— pushing coffee from faraway places. Noerbro is the go-to for your falafel, your student bar or even more increasingly than ever, your fancy restaurant. Kids run back and forth along the dusty square, kicking their football, shouting Wallah! As police cars, emboldened by stop and search laws, drive slowly down streets with brown and black children.

It is in Noerbro that you will see posters that declare “Eat the Rich”, while you grab your injira or even enjoy a cold bottle of white wine sitting not too far from Kierkegaard’s grave. With the high concentration of Muslims, history in activism and rebellion, Noerbro is ground zero in Denmark’s incessant wrestling with its pathological white ethno state yearnings. This is the battleground.

Right around the corner from this vibrant street is a classroom where I now teach. My students young adults, with names like Thor, Zeinab and Hussain.

One morning, as I stepped out of the bakery with my usual cortado, I stumbled. It was early, and the winter sun shone brightly on the lake. The streets were empty, aside from the usual congestion of bikes, parked on the sidewalk, leaning against buildings like workers at rest. I looked down to see what I had tripped over, and discovered a brass-colored plaque, in place of a cobble-stone. The plaque read:

“Here lived Pinkus Katz

Born 1875

Deported 1943

Theresienstadt

Died 15.3.1944”

Pinkus Katz? Who was he? And why was there a plaque, commemorating where he lived? And where had he been deported to?

***

If for some reason you were to end up in my classroom, one of the first things you’d hear me say is that although I’m your teacher, I expect to learn from you as well. For me, the optimum classroom is like an intricate ecosystem, where under the best circumstances, each element can blossom and thrive at what their particular strengths are.

I see my role as teacher as being one of a “conductor”- both as in the physics sense and as in the musical. It doesn’t matter if you’re from a Copenhagen suburb, or a country on the other side of the globe—we all have things we can teach others, stories to share. In a world that is currently battling a pandemic of social isolation, human to human contact, feeling as if we are part of a community is the best antidote.

I don’t want to suggest my classrooms have been perfect ecosystems of learning, however. My classrooms are within a system (the school) and whatever happens in that system, affects my classroom. This system is part of another system (the ministry) – an even larger one, that in a sense, one could argue, belongs to an even larger system (parliament). If one were to draw these systems, and how they are in relationship to each other, I suppose the diagram could resemble a rosete, with each smaller system, radiating from a common center, each new and larger growth encompassing the smaller ones. But what would this common center, from which it grows, be?

A crude example of how systems within systems affect each other, would be the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ which is a direct result of our western military and political decisions. This can look like the young student who has found herself in my classroom, fleeing the War in Syria and learning that her education has been rendered meaningless here. She attends school to get on track, but as she is about to finish up said education, changes are made in parliament which means there is still more for her to do before she can be accepted into Danish society by way of her employability. Or it could be a Danish student, whose parents had to flee Chile, during the U.S. sponsored military dictatorship of Pinochet. Or the young Afghan student, who you will learn walked to Denmark from his motherland, like so many other young boys whose parents sacrifice them, in desperation, hoping that the world will receive them, love them and support them in ways all humans should. But due to budget cuts made on the parliamentary level, have now found themselves having to be in a classroom despite crippling anxiety, and lacerations across their thin arms.

But it’s not about perfection in my classroom anyway. I’m looking to create a space where all of my students feel, even with crippling anxiety, in the very least, comfortable. I strive to do this through mutual comprehension: through our own innate desire and need to understand be in community with each other in spaces of love– storytelling that is centered around perspectives and experiences, using the power of counter storytelling to heal.

What many of my past students have had in common, no matter their origin, was a high level of unresolved trauma. It could be the emotional shock of war, the distress of displacement, drug abuse or even feelings of extreme emotional alienation, which could lead to other issues, including health. It could be any number of countless things that whether in isolation or cumulatively can render one’s nervous systems unable to meet even basic everyday routines like showing up to class. My number one priority as a teacher has always been to have a space where you feel valued and safe as this is not only integral to learning, but to living.

***

“Does anyone know who Pinkus Katz is?” I ask the three students who had bothered to show up that fateful day that I “met” Pinkus Katz. The classroom is a collection of crooked desks and Ikea furniture.

“Nope.” Says A – a young Palestinian who is working on his essay about his favorite popstar, a Miami-based Cuban who looks like a twelve year-old wearing too much make-up. He is smitten and tells me he will marry her because, “She’s so beautiful, Lesley. She will be my wife!”

There’s Z who’s always the first to show up and parks herself in the far corner of the classroom, usually with her headphones over her ears and phone in hand, where she would then proceed her blossoming career as a reader of all things internet – although serial murders is her favorite subject. Z tells me stories about Moroccan history, and about her Berber culture’s resistance to colonialism. Her long, curly black hair cascades down her face, a ‘do-not-disturb’ curtain of privacy. But I disturb. She shakes her head at me to let me know that she too has no idea who Pinkus Katz is.

Then there’s F – who I’ve learned all about the intriguing world of lip injections, for although she is legally too young for such a procedure, is an enthusiast by the looks of her perpetually puckered lips. F is a soft-spoken Kurd from Turkey who wears nails that look like daggers.

Her short, tom-boyish hair is usually tucked behind her ears, and although she holds herself back, I can tell that she likes being with us in class by the way she sits up, always at attention, unless of course, she’s checking her phone which by the looks of it, is her mostly looking at herself with puckered lips. “I’ll look it up!” She says, as she expertly types something into her telephone, in a way that showcases her fabulous nails. “Oh, found it!”

We all gather around her as she reads in Danish from the website. We learn that what I had stumbled upon was a stublesten – stumble stone – which was started in Cologne by the German artist Gunter Demnig who wanted to honor the Nazi victims of that city. The first stones were placed in that town, in 1992. But what started as a local project, soon branched out, and has grown to be Europe’s largest decentralized commemorative projects. The term “stumble stone” speaks to the idea that the artist wants us to “stumble” over these stones, like I had done that morning, and so “stumble over history” and be reminded of the people whose last address, before they were taken away, was here in Denmark.

We learn that Pinkus Katz, who was a shoemaker, was born in Russia and married Rebekka Duksin. In 1908 the family arrived at Copenhagen, with their two young children in tow. The family would eventually grow to include four more children.

On the evening of October 1, 1943, he and his family were arrested right at the place where I had found his name, right around the corner from where I taught English, right outside from where I purchased my fancy coffee.

The Katz family were taken to the ship Wartheland which was at the harbor here in Copenhagen– interestingly, the same one that hosts the statue of the Little Mermaid, that thousands of tourists flock to every year.

Once on the ship, he met his oldest son Salomon Katz, his wife Chaja and their daughter, who had also been arrested. It was a late evening on October 5, that they arrived at Theresienstadt. Pinkus Katz died on March 15th, 1944 after a battle with illness in the ghetto.

“Do any of you know what was happening here in Denmark during that time?” I ask, while I walk back to the computer on my desk to begin looking into this story more closely.

“The German occupation.” Z says, now also safely back in her seat.

“So he and his family were arrested at their home, and taken to a concentration camp?” A asks, a look of disbelief on his face. I shake my head and we all allowed the silence to absorb the heaviness in the room.

One of the stories you hear about the Second World War and the Nazi occupation of Denmark is that Danish people were able to smuggle 7,300 Jews to Sweden– a country that had offered refuge to them. Unfortunately, roughly 500 of them were not so lucky. Like Pinkus Katz and his family, they were deported to Theresienstadt, in Czechoslovakia. Theresienstadt was a Nazi front, which they labeled a “Jewish Spa” to lure elderly Jewish people. The word “spa” was used to obscure the true nature of the ghetto which was designed to encourage death. Theresienstadt was “part of the Nazi strategy of deception. The ghetto was in reality a collection center for deportations to ghettos and killing centers in Nazi-occupied eastern Europe.” (source)

“There were concentration camps in Africa,” A, a young Somali says, as she leans her back against the wall. A is striking, reminiscent of a high fashion model. “The Italians had concentration camps in Africa – from Libya to Somalia”, she teaches us.

***

While I’ve always been suspicious of “authority”, I’ve been just as leery of “hierarchy”. The idea that certain forms of life are more important than others seems ludicrous to me, granted that I have been inculcated with human supremacy. Such a thinking inevitably leads to families being carted away to death camps and contributes to the current turmoil that our world seems to be in. I noticed the other day that being anti-authoritative has been classified as a mental disease. But don’t worry, so is checking the ingredients of the food you’re about to purchase.

This distrust of authority makes sense to me, given that my historical legacy includes a system devised by a certain group of humans that racialized populations in order to subdue them, under an alleged and constructed “authority”. This system has its roots in the same mentality that sought to systemize and classify plants and the animal kingdom, placing the African on its absolute lowest strata, ala Linnaeus. This system that quantifies the body count, this system that places one form of life above all others.

Even as a child, this attempt at hierarchical ordering seemed ludicrous to me. Even growing up in the concrete jungle of Brooklyn, I could see evidence of the power of nature through the many trees I would have to pass on my way to school, or even in the dandelion weed, that pushed through the cracks of concrete, teaching me, when I beheld its tenacity, who really was boss. When we all have passed through this planet, when we have all passed through this dimension, when we all have finished what it was we had come here to do, tell me, to where do our bodies return?

Hierarchy?

I guess if we were to truly adhere to such ideas, the winner would be dirt, then. Don’t you think?

Leave a Reply